Dale Allison's Provocative Thoughts on the Resurrection

What does one of the world's top experts on historical Jesus have to say about Jesus' resurrection? Here's why his thoughts are not only provocative but worth knowing about.

(Image: Midjourney)

Easter is just around the corner. There’s no way around it: Easter is primarily, historically, and culturally not about egg-related customs, or dousing combined with whipping (yes, it’s still a thing where I come from). Instead, it’s about the resurrection of Jesus. But why, in such a lawlike universe as ours, would anyone accept it not just metaphorically, but as a historical reality?

Reasons for God and Jesus’ Resurrection

I’m not aware of a poll that specifically asked about the reasons people give for their belief in Jesus’ resurrection. Nor am I aware – with one exception – of a survey that would ask people about the reasons for believing (or disbelieving) in God. Of course, there are plenty of polls that regularly survey religious demographics, but these don’t include (as far as I’m aware) questions about the reasons behind their belief. The one exception I know of was carried out in 1998 by Michael Shermer (editor of the Skeptic magazine) and Frank Sulloway and is summarized in Shermer’s How We Believe (2003). The polled sample is not completely random, however, and consisted of c. 1,700 respondents to the Skeptics Society survey. Unless I’m mistaken, I take it that it was conducted among the readers of the Skeptic magazine. This included both believing and non-believing skeptics, as seen below. Here’s my summary of the results:

Why skeptics believe in God:

argument from design (29.2%), comfort, solace, purpose (21.3%) experience of God's presence (14.4%), need to believe in something (11.4%), no morality without God (6.4%)Why skeptics think other people believe in God:

comfort, solace, purpose (21.5%), need to believe in an afterlife (17.8%), lack of exposure to science or education (13.5%), raised to believe in God (11.5%), argument from design (8.8%)Why skeptics don't believe in God:

no proof for God (37.9%), no need to believe in God (13.2%), absurd to believe in God (12.1%), God is unknowable (8.3%), science provides all the answers (8.3%)

But while there hasn’t been any similar polling about the resurrection, I’d suspect that, for most, many of the reasons would overlap with at least some of those given by believers above. That is, people accept Christianity because it is a compelling, gripping, and meaning-making narrative, giving hope, joy, and light to our past, present, and future. It’s a story of forgiveness, reconciliation, and redemption. It’s a plotline where we’re not just the readers of that plot, but actors playing crucially important parts. It’s no small thing that it comes with the promise and hope of an afterlife. And such a sense-making explanation makes sense. Who wouldn’t like to be a part of such a story which is about meaning, hope, and love? Christianity captures many hearts and minds because it comes with the resurrection and all its meaning-making benefits. But are there other reasons too? Reasons that would be specifically of a historical nature? We all know the answer to that question – you bet!

Naturally, there have been many apologists as well as bonafide scholars with a relevant background in history arguing for the resurrection of Jesus. Usually, it’s been a contest between those favouring the historical evidence to show that Jesus rose from the dead versus those claiming otherwise. I’ve been following these debates (on and off) for at least the past 15 years or so, and I’ve never found either side compelling. My (completely unoriginal) view is that the reality of Jesus’ resurrection can’t be decided based on historical facts alone. There are other things that matter too. Also, it won’t be the last time that we make this observation here.

But in my following these debates, it’s been typically the case of one side arguing (rather confidently) for or against. There never seemed to be someone who’d be, so to speak, holding the middle ground. And while I think I know personally a few other prominent scholars who would occupy such a position, they’ve never been vocal about it and engaged in these resurrection debates. But there is at least one such exception and scholar par excellence – Dale Allison.

Allison: All Alone in the Middle

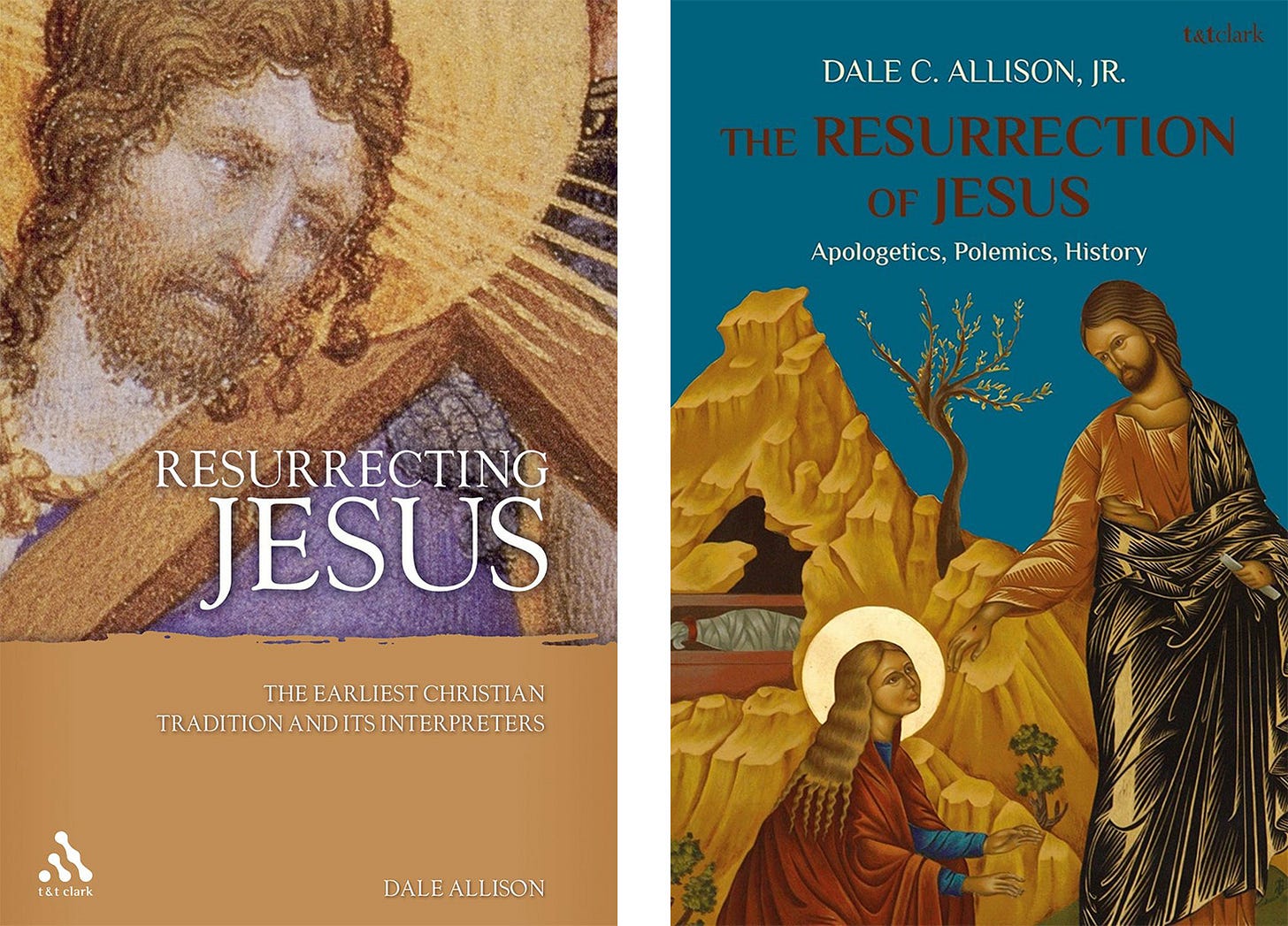

Dale Allison is a prominent New Testament scholar, professor at Princeton, and the author of many books on historical Jesus. Two of these books are directly concerned with our topic at hand: Resurrecting Jesus (2005) and The Resurrection of Jesus (2021). Luckily, you’ll find a lot of YouTube content featuring Allison, and so that’s one way of learning about his ideas. Recently, he’s also created this online course on historical Jesus that I’d recommend. By his own admission, he’s a church-going liberal Christian (‘I’m a Christian … but of a liberal sort’) and we’ll have him talk more about this later.

Dale Allison (Image: Princeton Theological Seminary)

Here’s the reason why I think Allison is worth listening to for anyone seriously concerned with the historicity of Jesus’ resurrection. His thoughts are provocative because he stands, in a way, in the middle. As you can imagine, that’s rarely a very peaceful position in a heated debate. If you like chocolate ice cream and your friend likes vanilla, then you might disagree on which flavour is ‘objectivelly’ the best one. But if I come then and say, ‘You know, there are more flavours than just chocolate and vanilla and so it’s a bit more complicated,’ then I’ll have not one but two sides that wouldn’t like my view. If you ask me, that’s kind of where Allison stands on the resurrection. As he himself admitted:

I'm always in the middle, all alone. But I got used to it. My wife loves me.

But I should emphasize that many on both sides have praised him exactly for his critical rigor and impartiality. For example, William Lane Craig, the foremost Christian apologist, praised Allison’s balanced treatment of the resurrection as follows:

I’ve never seen a better presentation of the case for scepticism about Jesus’ resurrection than in Allison’s Resurrecting Jesus: The Earliest Christian Tradition and Its Interpreters (New York: T. & T. Clark, 2005). He’s far more persuasive than Crossan, Lüdemann, Goulder, and the rest who actually deny the historicity of Jesus’ resurrection. That Allison should, despite his sceptical arguments, finally affirm the facts of Jesus’ burial, empty tomb, post-mortem appearances, and the origin of the disciples’ belief in Jesus’ resurrection and hold that the resurrection hypothesis is as viable an explanation as any other rival hypothesis, depending upon the worldview one brings to the investigation, is testimony to the strength of the case for Jesus’ historical resurrection.

That’s, I think, a good summary, but already here, there’s one important distinction that needs to be made: While Allison might see the resurrection hypothesis ‘as viable an explanation as any other rival hypothesis’, he doesn’t see it as a viable historical explanation. We’ll come to this point momentarily when we let Allison speak for himself.

Before we do so, we should acknowledge that we all have our biases and in that sense, we aren’t impartial. No one is and neither is Allison. But at least in his historical treatment of the resurrection narratives, he probably comes pretty close to impartiality (in my not-so-impartial view). So what does he say in his books about the value of historical investigation in bringing us to accepting the resurrection as a historical reality?

Allison in the Books

In both of his books (Resurrecting Jesus and The Resurrection of Jesus) he offers an almost identical section called ‘Coda’ where he sums up his thoughts on historical exploration as related to Christian belief. It’s very short, on three or two pages, respectively. Here are a few takeaways:

Historical investigation will not hand us theological conclusions and such efforts are ‘frustrating.’

This ‘frustration’ is evident not just for historians today, but ‘has an analogue of sorts in the Gospel accounts of the resurrection.’ There are several instances where the disciples either doubt in the historical Jesus and can’t recognize him despite seeing him (Matt 28:17, Luke 24:30-31, John 20:11-18, Acts 9:7).

It’s not all about seeing and being a historian: ‘Sight is not insight; knowledge is a function of being; and religious knowledge must be a function of religious being. As the beatitude has it, "Blessed are the pure in heart, for they will see God." This last is an epistemological statement, and it implies that we require more than history if we are to find the truth of things.

Ultimately, it’s not about history at all but about human experience and faith: ‘Maybe then it is not so surprising that most who believe in Jesus' resurrection, however exactly they understand it, have as little need for modern historical criticism as birds have for ornithology. When Christians, on Easter Sunday, greet each other with the acclamation, "Christ is risen," the expected answer, "Christ is risen, indeed!" is not a statement about investigative results. ... Although ignorance should not be the mother of devotion, true religion nevertheless involves realms of human experience and conviction that cannot depend upon or be undone by the sorts of historical doubts, probabilities, and conjectures with which the previous pages have been concerned.’

As we’ll see, these thoughts will be echoed in some of his interviews where he commented on his books as well as criticisms he’s received. But is there something we learn about worldview? Yes, we do. In his The Resurrection of Jesus, he has an interesting section, where he talks about his multiple, four-fold personality:

I am, more significantly, a multiple personality. One self is pious. He says his prayers, goes to church, and tries to think theologically. His conscience is the New Testament. He venerates the great mystics, is at home in the Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom, and writes books such as The Luminous Dusk and Night Comes.

This character, however, lives alongside a critical, hard-hearted historian who knows how tough it is to apprehend the past, and how easy it is for one’s theological patriotism to get in the way. He knows that the fear of self-deception is the beginning of wisdom, and that “Abandon all certainty, ye who enter here” is the sign over the door to history. ...

Another inner voice, near kin to the wary historian, belongs to the I Don’t Know Club. He is relentlessly skeptical about almost everything, including know-it-all skepticism. ... He knows that people are always more often in error than they are in doubt, and that he cannot be the exception. ...

Yet another inner self is a Fortean. … He is incredulous that anybody’s worldview should be the final arbiter of reality. Proselytizing rationalists, who have the explanation for everything in their all-purpose, reductionistic bag of tricks, impress him no more than the magician who pulls a rabbit out of his hat. ... He holds that reality, full of magical surprises, does not obediently stay between the lines drawn by the self-appointed gurus of consensus reality. ... This countercultural fellow does not believe that the world is a reasonable place in which everything has a reasonable explanation.

All this is helpful, but still, it might be difficult to gauge what he thinks about the resurrection. There are a few snippets. For example, in Resurrecting Jesus, he writes:

although I think that the tomb was probably empty, although I am sure that the disciples saw Jesus after his death, and although I would be personally delighted to espy dramatic divine intervention in the world, I remain unconvinced [that the literal resurrection of Jesus provides the best historical explanation of the data].

Allison Beyond the Books: On Resurrection

But just from his books, it might not be immediately clear what he personally believes about the nature of Jesus’ resurrection. Thus, it is helpful that he provided some further comments in some of his YouTube interviews. One of these was on Paulogia where he was asked to provide his clarification on the resurrection. You don’t need to watch the entire interviews and, instead, you can read the relevant transcriptions provided below.

Here, Allison talks about his own view on the resurrection. He believes that Jesus’ tomb was found empty, but he’s not sure how to connect this event with theology (3:45-4:31):

I'm happy to say that I think the tomb was probably empty, but the weird part of me is that ... I'm not sure how to connect [it with the resurrection]. So, for me, life after death and victory over the grave aren't going to have anything to do with an empty tomb for anybody else and so it's really odd for me to know what to do with Jesus's tomb ... . I just don't know quite what to do with it in my own thinking. So when I say I think the tomb was probably empty I think I'm really doing that as an historian because I don't I don't know what to do with it theologically. I'm there not a traditional Christian. It's just a mystifying thing I'd be just as happy without it; maybe happier without it.

He goes on to respond to the charge that while he’s not a post-modernist, he’s influenced by post-modernism (4:53-6:39):

I am an old-fashioned follower of Socrates and Socrates correctly interpreted the Oracle of Delphi: The wisest person in the world is the person who knows he knows nothing. That's not a post-modern take. That's somebody from the ancient world who's looking around and realizes that things are very complex, very complicated. We have finite minds and we don't understand a lot. And for me, it's actually worse because I'm a Christian … and I'm very attracted to apophatic theology. I'm really attracted to the parts of the Christian tradition that are mystical; I'm very attracted to liturgical lines which refer to mystery. So no, this is not post-modernism. This is, I'd like to think, genuine traditional epistemic modesty. It also comes from reflecting upon the fact that I have certain academic heroes and people that I admire and these would include … Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Augustine, Pascal, Gregory of Nissa, and you could come up into modern times. You could put John Locke, maybe you want to put Einstein in the room. Aldous Huxley is one of my favorites [as well as] William James. You put them in a room and ask: “What do they all agree on?” So, these are my heroes, these are my lights, and they disagree among themselves on absolutely everything. So the notion that I, sitting here at my little studio, have figured everything out is actually preposterous. It makes no sense to me whatsoever. So I'm just grasping … at little pieces. I don't have the whole picture of anything and this is genuine and heartfelt and has nothing to do with post-modernism.

Not By History Alone

As we saw previously, he makes it again clear why history can only get us so far. There’s always an epistemic leap, based on other considerations, that one needs to make either to accept or reject the resurrection (7:30-8:34)

I, as an historian (and as I argue in the book), say that I think that a Christian can look at all the evidence and feel okay. And I think that a skeptic can look at all the evidence and feel okay – by which I mean be unmoved … to change your mind. So the idea that an atheist could objectively just study history and be converted to the belief Jesus rose from the dead doesn't make sense to me, even though occasionally someone will say that. And then the other view doesn't make sense to me – that you believe in Christianity and then you just read historians and you think purely like an historian and you make a decision that could never have happened. I think other things are always at play here – philosophical issues are always at play, social psychology is always at play, your family history is always at play, everything's at play and people aren't making your pure historical moves. And if they were capable of doing so, I personally don't think from where I stand that they're going to get very far.

There are a few other excerpts below from the following interview on Potential Theism where Allison reiterates his basic points, although in different words:

On his view, it’s difficult, if not impossible, to convince a skeptic that Jesus was resurrected just by examining history (2:55-3:58)

How strange is it that people can go back 2,000 years and look at our or five sources [the gospels and the apostle Paul] ... and convince an uninterested audience or an open-minded person exactly what happened. I don't think it's very likely that that's going to be the case. ... I end up concluding that if you want to take a Christian interpretation of these events, nothing prevents you from doing so ... [but], on the other hand, ... I don't see how you can prove to a skeptic that Jesus was raised from the dead.

Indeed, such a conclusion is not for historians to decide (4:13-5:42):

I think that your view of the Resurrection isn't going to be determined simply by historical considerations. I think there are all sorts of other things going on, for example, I know that there are many people who don't believe in miracles, and for them, that's just a surety they don't happen. That's it. And if you start with that I don't see how the evidence in the New Testament is going to overthrow that in and of itself. There are larger questions here besides the historical evidence from the New Testament there are larger questions about the nature of the world, the nature of God, if there is a God, what can and cannot happen in the world, what does and does not happen in the world and so on. There are just so many other questions and they influence how you construct the data, how you interpret the text, how you approach everything. So when you take that into mind, it's not confusing at all that there's a spectrum of opinions and different explanations and so on that's just what you would expect from what is, in essence, an event that took place 2,000 years ago for which we do not have an abundance of evidence. It's nothing like the Kennedy assassination, and as I said, I'm still kind of uncertain about what exactly happened on that occasion.

The historical data don’t force a historian to choose a particular position on the resurrection (11:27-11:58):

The point is that you can take the data and you can interpret it, or configure it, in multiple ways. So for me, the big question, after you get done with history, is worldview, and what you think of God, or what are the possibility of miracles, and so on and so on. But the historical facts, the data you can uncover, do not seem to me to force you to be a skeptic and they don't force you to be a Christian of some sort.

Here, Allison was asked what he thinks about the nature of Jesus’ resurrection and what he’d reply to those who might question his Christian faith (15:36-17:40):

I would hope that people would respect my conviction that I am a Christian: I teach at a seminary, I go to church, I'm very pious in my own ways, I have a rather lengthy and complex prayer and meditation routine I'm involved in every day, I've spent my whole life studying Christian scriptures, my favorite people in the world are all Christian figures. So I don't really understand this sort of slander. But maybe I'm just confusing because maybe there are people out there who don't think that liberal Christians can be Christians or somebody like me who can say: "Well, I think the tomb was empty and if God did it fine; if it turns out not to be empty then that doesn't trouble me." I personally have philosophical questions about the relevance of human bodies in the world to come or in the afterlife and I'm just being honest about those questions and my doubts. So I just end up being confused about some things but I'm confused about lots of things. I'm not certain about very many things. I have lots of hopes, I have lots of dreams, I have convictions, but I'm sure I'm wrong about many things. And if somebody wants to say, well, he can't be a Christian because he's confused about what exactly risen bodies are or he doesn't really want the tomb to be empty or thinks it might be okay theologically if it wasn't... Well, look that's for other people I guess to to worry about. I'm just being honest that's all I'm doing.

In the end, I think it’s fair to say that Allison’s thinking and conclusion can be boiled down to this simple statement (41:26-42:12):

'The are multiple options here. There's also just the option of saying, This is really interesting; I'm not quite sure what happened. And I think somebody who is educated and well-informed can do that. And then probably what they think about the text or this tradition or this story is going to be dictated by things beyond their historical excavation uh Christianity is much larger than just just what you can prove historically how could it not be? Heck, Christians believe in God! How do you prove God historically? How do historians establish that there is a God makes no sense.

Important Lone Voice?

So, what should we make of all this? That’s, of course, a question that’s left up to each of us. In my view, Allison provides a doubly skeptical, yet reasonable, erudite, and cautious voice in the resurrection-debate wilderness. As must be clear, there are many other writers who have pointed out the importance of the worldview assumptions we bring to the debate. If one already believes in God who is, at least in principle, capable of resurrecting Jesus, then that can be a real game-changer. But, in Allison’s estimate, it doesn’t work the other way round: the gospel stories (and Paul) by themselves can’t demonstrate that Jesus was resurrected and that, in turn, there must be a divine Resurrector. These seem to be two different strategies: Do we have to start with God or can we start with the gospels? It’s quite clear which side Allison favours. And while we can’t simply choose by pressing a mental switch which strategy we prefer, we can – and perhaps should – reflect upon them. I think that if we met Socrates, he’d have a few questions about why we accept or reject Jesus’ resurrection. Perhaps in such an encounter, our answers might turn out to be not thoroughly thought out.

Enjoy your sips,

Andrej

A really wonderful post, Andrej! I am a massive fan of Allison's judicious approach to the resurrection. You summarise it really well here.

As much as I respect Allison for his accomplishments and willingness to hold his ground when Christians and academics look to him for clearer answers, I often worry that he's making an argument to moderation because it allows him to somewhat exist in two worlds simultaneously, even if he's partially rejected by both. Having read quite a bit of Allison's work, I am frustrated by what feels like a miscounting of the totality of evidence on both sides. On one side, we have (1) our understanding of the absolute determinism of the everything existing, precluding the possibility of bodily resurrection of the dead, (2) an analysis of the gospels and NT epistles as literature, including how their authors make use of genre, tropes, motifs, etc. to paint a picture of a deified martyr. On the other hand, we have ... tradition? I get that the methods of historical analysis have no way of confirming or denying reported miracles in the past. But that does not mean that no method is capable of assessing the probability of a particular miracle.